Weifang (Shandong) – Japanese Internment Camp

Before arriving in Shandong Province and searching for the memorial to Eric Liddell, I had read a fascinating account of life in the Japanese internment camp by author Langdon Gilky called “Shangtung Compound” (1966). He discusses in detail the internal struggles among the foreigners who were imprisoned here for 2-3 years prior to the end of the war with Japan. He also includes sketches of the camp layout, its buildings (check my photo album), and different aspects of life in the camp. The book is great reading.

One of the people he discusses briefly, but with great respect, is someone he calls Eric Ridley (he changes the names of all of his characters). In the context of resolving a major problem of families with their teen-age youth in the camp, he writes: “The man who more than anyone brought about the solution of the teen-age problem was Eric Ridley. It is rare indeed when a person has the good fortune to meet a saint, but he came as close to it as anyone I have ever known. Often in an evening of that last year I … would pass the game room and peer in to see what the missionaries had cooking for the teen-agers. As often as not Eric Ridley would be bent over a chessboard or a model boat, or directing some sort of square dance—absorbed, warm, and interested, pouring all of himself into this effort to capture the minds and imagination of those penned-up youths.

“If anyone could have done it, he could. A track man, he had won the 440 [yards] in the Olympics for England in the twenties, and then had come to China as a missionary. In camp he was in his middle forties, lithe and springy of step and, above all, overflowing with good humor and love of life. He was aided by others, to be sure. But it was Eric’s enthusiasm and charm that carried the day with the whole effort. Shortly before the camp ended, he was stricken suddenly with a brain tumor and died the same day. The entire camp, especially its youth, was stunned for days, so great was the vacuum that Eric’s death had left.” [p 192]

In reflecting further on the larger group that Eric was part of, he writes: “There was a quality seemingly unique to the missionary group, namely, naturally and without pretense to respond to a need which everyone else recognized only to turn aside. Much of this went unnoticed, but our camp could scarcely have survived as well as it did without it. If there were any evidences of the grace of God observable on the surface of our camp existence, they were to be found here.” [p. 192]

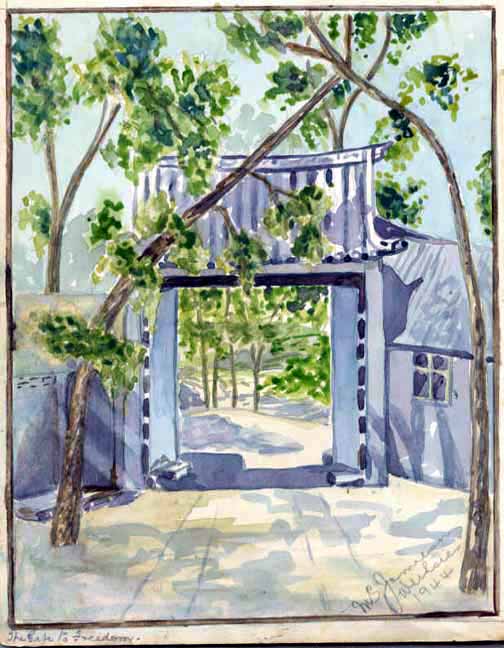

I walked through the former mission compound, LeDaoYuan (or Courtyard of the Happy Way) now celebrated mostly for its history as a Japanese concentration camp. My new Chinese friend (the English teacher) reminded me of the Chinese people outside the camp who risked reprisals from the guards for smuggling food and messages to the prisoners. Indeed, there are many stories to be told of the heroic actions of Chinese people during this bitter time of their own history. Gilky recounts one episode [p. 170] where two Chinese farmers were shot by the Japanese for “trading over the wall” of the camp.

Hundreds of foreigners, mostly from Beijing and other points in the north of China (including hundreds of students of the Chefoo International School in Yantai), spent many months here up to the time of the Japanese surrender. The Ledaoyuan mission and former liberal arts college was an ideal location to be taken over by the Japanese. It had numerous buildings, including classrooms, student dorms, a hospital, and various staff residences. It would have been surrounded by a wall, a common custom that continues in China to this day. The Japanese simply added barbed wire and sentry posts.

Today, the location is celebrated as the former Weihsien Internment Camp (also known as the Weihsien Civilian Assembly Centre). Tour groups come here, and the location is preserved with beautiful gardens. It continues to be a worthy location for both foreigners and Chinese to visit. Indeed, this is a place rich in history.

More photos are available here:

Weifang — Japanese Internment Camp

Related blogs:

This article is one of a series relating to my visits to Shandong Province in 2013 and 2016. Use links below to access related blogs:

1 – Eric Liddell – Early Olympic Hero in China

2 – Weifang (Shandong) – Historic School and HospitaL

3 – Weifang (Shandong) – Japanese Internment Camp (current article)

4 – Shandong University – Its Early Years

5 – History of Western Education in Shandong (under development)

This blog was adapted from East Meets West 03 — Weifang’s Japanese Internment Camp, published by the same author on the Hunan Government English language website, 3Us, at:

http://forum.3us.com/thread-64382-1-1.html [No longer supported.]

First published: 2016/11/09

Latest revision: 2023/04/08